Foreword by Dr. Ian Treklin

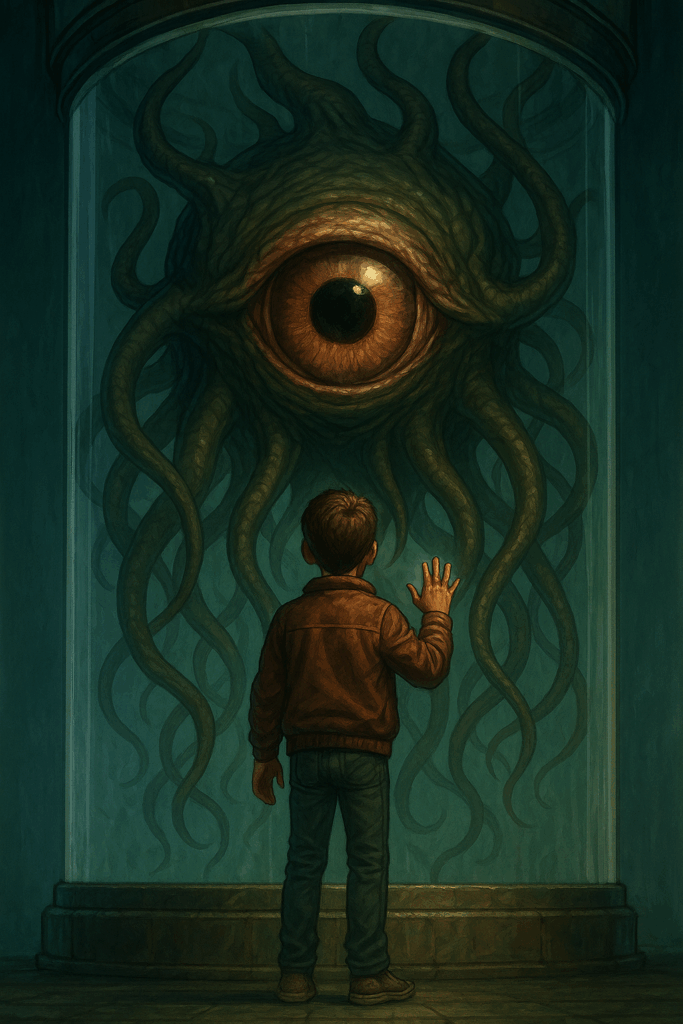

When I was nine years old, my mother took me to the xeno-zoo in Highhill, Ark-Khel. It was a civic jewel then—polished corridors, suspended walkways, the thin hum of climate baffles massaging air that smelled faintly of antiseptic and starfruit. People came to marvel at fauna that should have remained rumors. I came for one exhibit only: the specimen labeled, with the crisp confidence of bureaucracy, Containment 7 — Unknown, “Spawn.”

The First Encounter

Its enclosure was a cylindrical tank—a full 360-degree column of reinforced silica and field-lattice, embedded floor to ceiling so that the creature seemed to hang within the architecture rather than in a room. The crowd moved around it the way a clock hand travels: orderly, curious, certain that the second hand would advance. I remember the creature’s silhouette only in fragments—an arc of tendon here, a laminar ripple there—as if my mind could not hold its total geometry at once. But I remember how it watched. Not with eyes, exactly, but with attention so specific that I felt it land on me like a weight. As I walked the perimeter, the thing traced my movement, not swiveling so much as reallocating. Near the end of the circuit I put my palm to the glass. It was childish and forbidden. Cold came up through my hand, and then—a pressure, like a word pushing through deep water. It was not a voice, and yet it organized itself as meaning. I had no referents for the grammar, no lexicon for the intent, only the unmistakable impression that the world on my side of the barrier had been addressed.

That night, I wrote my first notes: It spoke in a language I did not yet understand.

New Annapolis and the Academy

Years later, the Academy of Sciences in New Annapolis gave me the tools to pursue that “yet.” The Institute’s Militarized xeno-weaponry program was an uneasy marriage between observation and destruction: microscopes beside missiles, spectroscopy beside lasers. The faculty insisted on definitions; they also taught us that definitions are wagers. I learned to assay tissue that refused to be tissue, to measure fields that bent our instruments as if instruments were suggestions. The word Spawn persisted in public reports, but in our lab books we wrote cautiously:

- Non-anthropic self-ordering system (NASOS)

- Extranomic attractor

- Ocular manifold

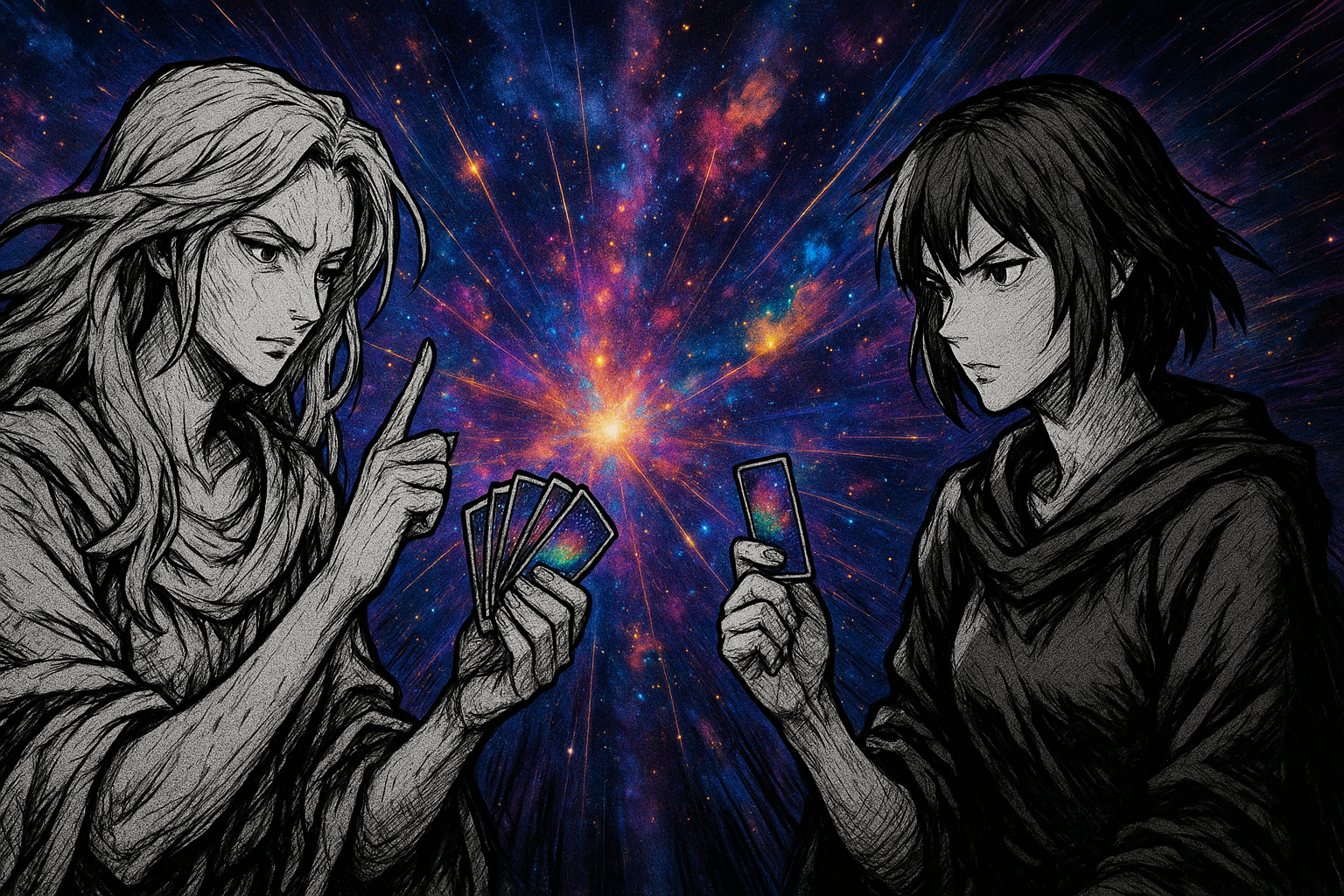

Naming the Unnameable

I am often credited—sometimes blamed—for the naming scheme that followed. I chose to organize the observable families under the borrowed scaffold of human taxonomy not because it fit neatly, but because it forced us to state where it failed.

- A kingdom asserts boundary; a Spawn dissolves it.

- A genus presumes inheritance; a Spawn appears to recurse upon itself without time.

Latin gave us a neutral tongue from which to coin without parochial superstition. And so, with apology to dead botanists, we drafted:

- Regnum Exoperfecta

- Phylum Oculata

- Classis Nulliformes

- Genus Oculus Exo-Perfectus — the Perfect Eye from Outside the Order

The Divine Error

The seminarians in our cohort complained that the name sounded like flattery. It is not. Perfectus here means “completed”—a system closed upon itself. Such closure, imposed upon an open cosmos, manifests to us as error: a contradiction that persists, repairs itself, and extracts a cost from local reality to maintain its completion. Hence the title of this book: The Divine Error.

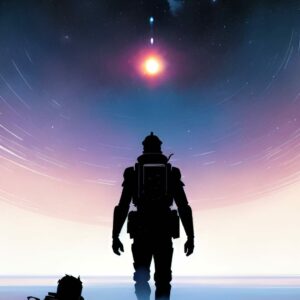

The Experiment

My colleagues and I were young enough to believe that understanding confers leverage. Our early projects in the New Annapolis Complex paired classification with countermeasure. The experiment that marked me—literally and otherwise—concerned a juvenile specimen no longer than a forearm, harvested inert from a dead field on the Talamile wrecks.

At 03:17, a null flare—too brief for our recorders to agree upon—passed across the chamber. All readings zeroed; not flatline, not overflow, but a kind of unsaying. In that unsaying, the specimen became motion. My team were living men and women, leaning into their instruments, and then they were… not. The chamber remained sealed. The lights, green. Why was I spared? My gloved hand was against the glass, taking a thermal gradient. I felt again that pressure from Highhill—dense, directed, entirely aware—and the error simply refused to cash me out.

Purpose of This Book

This book is my contribution to a different wager—that to name precisely is an act of containment more rigorous than any tank.

- Part I gathers observations: motion without momentum, gaze without geometry, influence without contact.

- Part II presents the taxonomy and its working terms, including the rationale for Oculus Exo-Perfectus.

- Part III is procedural: how to see without summoning, how to measure without flattering, how to build cages that do not become altars.

- Part IV addresses meaning—not as solace, but as inevitable byproduct of attention.

A Final Appeal

If you purchased this volume to find a weakness you can strap to a missile, close it and return it. There are cheaper ways to die with colleagues you love. If, however, you are prepared to practice a discipline that is part science, part humility, and part watchfulness, then join me at the edge of what we can state. Look with care. Name with rigor. Do not assume the eye ever blinks.

I began with a child’s palm against glass. I will end with an adult’s: the skin wrinkled, the tendon scarred where the juvenile brushed me and left a line that will not heal. I press my hand to the page the way I pressed it to that tank. On the other side is attention. Whatever reads us back is not a god I can worship, but it is a truth I cannot ignore.

— Ian Treklin

Senior Scholar of the Academy of Sciences, New Annapolis